In an interview, Hong Kong activist Kaspar Wan talks about his experience of becoming a transman and the transgender rights movement in the city.

How and when did you start identifying yourself as a trans person?

I was an assigned female at birth and I realised that I’m a trans person in 2010 when I was 32. I read a biography by Ayana Tsubaki, a trans woman from Japan, called I Went to a Boys' School. When I read it, I was surprised by the many similarities between us, from how we think to how we feel. Like her, I always had another name in mind when I was small, which is my name now.

As the Cantonese saying goes: “three years old fixes 80”. One’s character is formed at a young age. When I read the book, I suddenly connected all the dots in my life. As long as I could remember, I had always wanted to be a boy and imagined how my life would be like if I was a boy. When I learnt about the trans identity, everything fell into place. I’m not a tomboy, I’m not a lesbian. Not that I “wanted” to be a boy, but I identified as one instead. I’m a trans and that’s me.

As a devoted Christian, how did you handle your identity transition in relation to your faith?

At around 28 years old, I met a girl and grew so fond of her that I couldn’t deny anymore. As a Christian, it really hit me because I was not a boy and I liked girl, did it make me a lesbian? Am I sinning against God? That would be the last thing I want. I would rather die than to sin against my God.

I then took some time to travel around Europe, with an incentive to find a place where no one knew me and stay there till I die. I didn’t want to exist anymore. I kept questioning my God why he created me this way – I had always wanted to be a boy since I was small, before I was fond of any girls. That time was very sad and depressing. After three months, I came back, felt a bit better but the bigger question – whether I was a lesbian or not, or whether I had sinned against God – was not resolved.

When did you reveal your realisation to your family and how did they respond?

It all happened within a month. In early September 2010, I told my parents that I’m not going to marry and that I like girls, then at the end of the month, I told them that I wanted to be a boy.

Before I came across the concept of transgender, the struggle had already lasted for two to three years, and I couldn't find another answer. So I thought: “If I am a lesbian, so be it.” I still remember I told my parents that “I like girls because I am a boy.” I didn't know how I came to this kind of logic, but the only explanation was that because I’m a boy.

My parents didn’t say much after my short message. But after a few days, my dad asked my mum what happened to me, whether I had a psychological problem. Then after a week, I read Tsubaki’s book and found out that I am a trans.

When I told my parents that I wanted to be a boy – which implied I would take some actions, my father looked at me for a while and said: “Well, this must be something you have longed for since you were small. But do sit on it.”

I brought my mum along to the first psychiatrist consultation. And it’s the first time she heard my full story. The psychiatrist also asked my mum what she thought. My mom said she actually thought of disowning me just to make me think twice. I did not know she had that idea, though I lived with my parents. They never said anything harsh or asked any questions. My mum finally dropped that idea because she was afraid of losing me if she said something against my decision.

Why drove you to go for a gender affirmation surgery?

Initially after reading Tsubaki’s book, I was happy to finally find myself and didn’t think about having a surgery. But I also recalled my many questions for God, so I was like: Alright, I don't want this issue to come between us. Maybe surgery is the way out.

And it actually worked, in the sense that I could have that peace of mind. And I no longer challenge God why I was not a boy but had a boy inside. God and I could co-create my life. That's how I decided.

Also, I wasn’t comfortable with my top part, so I had a top surgery and felt more like in my body. And I took testosterone, which deepened my voice and made me looked more like a man. So I’m very happy with the changes.

What were the medical procedures or hurdles that you had to go through to change your identity?

Compared to other trans, I think I had a very smooth transition – I read a book, I looked back at my past and connected all the dots. I became certain of who I am. I’m just so happy to find myself and to tell everyone: I’m not a lesbian, I’m a trans.

After the first consultation, the psychiatrist was pretty sure that I’m a typical binary trans and referred me to meet with an endocrinologist and a surgeon.

For the transition journey of a trans person, you could only know whether this is something you want after you take the step, because you can’t imagine the change even if you try to. Some may be happy with how testosterone can stop their period or change their voice, but then they may start losing hair. There can be many back-and-forth, many frustrations throughout the process.

Besides medical procedures, what are the other challenges you have faced during the course of transition?

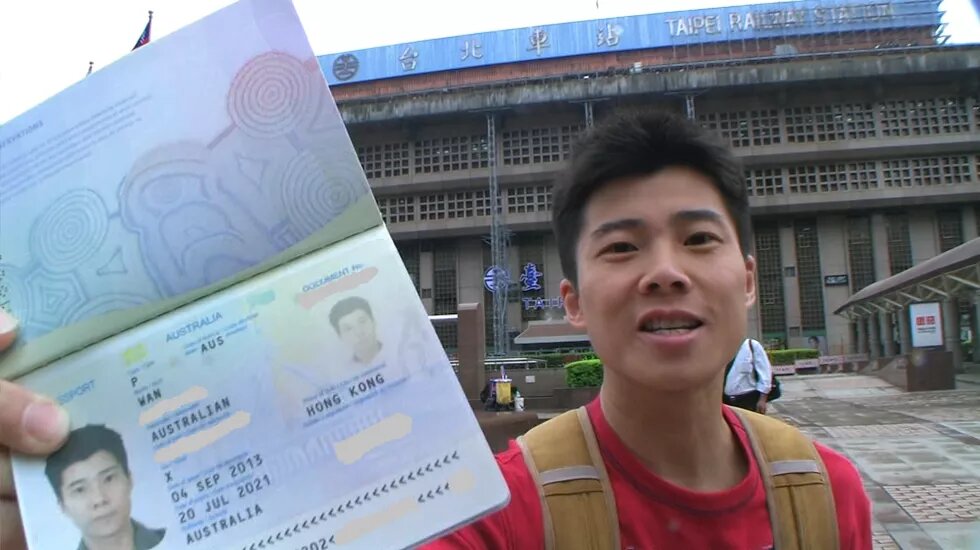

When talking about gender transitioning, there are multiple aspects, like social, medical, and legal. The physical aspect is about how you change your body; the legal part is about how we get recognition. Non-binary trans don’t want to be categorised as either male or female, but it’s not a legal option in Hong Kong. In some countries, people can identify as gender X on their ID card, like in Australia, the United States or Nepal, but not in Hong Kong.

For me, I can’t change the gender on my Hong Kong identity card. I often encounter issues when I present my ID card, because it’s incongruent with my masculine appearance. I am always prompted to explain, which is very inconvenient and uncomfortable, even stressful at times. The social aspects could be the most challenging part for a trans person.

Of all the struggles that you had been through in pursuit of yourself, which was the hardest?

Once I realise I’m a trans, I could put up with anything. It’s hard to say which is the most difficult, but whatever it might be, I could just get through it.

And this is something I’ve learned from my experience of being an assigned female, what trans people are going through is very similar to all the struggles in the women’s rights movement. Whether you have the power over that part of your body or not, how you look, whether you are addressed as a “Miss” or “Mrs”… it’s all about how you are being perceived and recognised.

When you first found your identity, what was the trans community in Hong Kong like?

A community already existed back then in 2010s, and it was accessible. There was one church that welcomed LGBTQ. It had more gay people, but had also gathered some trans.

It was also when Joanne Leung, a trans woman, was starting an organisation for trans people – so I was very fortunate. We got a small community of about 30 people. The community today is still quite small – maybe a few thousand, with only about a few hundred visible ones.

Do you know any trans who are considerably older and have undergone similar experience before you? How was it in the 80s or 90s in Hong Kong?

Hong Kong is probably one of the earliest places where [gender affirmation] surgery has been free and supported by the public healthcare system since the early 80s[1], so you don't have to scramble for money or fly to Thailand for it.

There was only one surgeon – Dr Albert Yuen Wai-cheung – who performed the gender affirmation surgery. He is highly respected among trans and many of us call him “the father” as he has given us our second life. As he once said in an interview, he was just a doctor and he saw that this group of people needed help, then it’s his medical responsibility to provide the service. Of course, he upholds strict standards on whether one is suitable for a surgery and would deny those who are considered not ready.

Socially, many trans have gone through a lot of struggles over the years. I know one person who did her surgery in the 90s when she’s 27 years old. She belongs to the earlier generation of trans. She was very happy with her second life herself, but a lot of her “sisters” [other trans women] were very miserable and many of them ended up in jail for drugs or prostitution.

In 1997, a famous trans woman who had appeared in many TV shows committed suicide and similar stories of trans suicides were reported a few times in the 2000s.

Throughout your years of trans advocacy in Hong Kong, what are the major controversies and how would you respond to them?

There’s the controversy of whether trans persons are fully informed before making the decision or whether they would regret afterwards, especially for young people. But what’s the worst consequence? Like for a young trans woman, her penis may not be fully developed because of the hormones used during puberty and she wouldn’t be able to have her own offspring. Biologically that would be the consequences of using puberty blocker. But as a trans, whether binary or non-binary, you have to own up to your decision, just like everyone else.

As a trans person who has been supporting my peers, I would say that giving as much space and as much information as possible to a trans person is very important. So that they would know about the consequences, know that they could take their time and are not rushed into making any decision.

What is the youngest case you have come across at your charitable organisation Gender Empowerment?

A 13-year-old. It’s about the start of puberty when they grew more anxious about their bodily changes.

For trans youth before puberty, only social transition is possible, like changing your name or pronoun, and nothing much about the body because no medical intervention is allowed and their body dysphoria may not have been so severe. After a string of assessment, an adolescent may be prescribed puberty blocker to buy more time before making the actual decision of further physical transition, in terms of the use of hormones and/or surgeries. It can help alleviate or even prevent symptoms of gender dysphoria. Of course, the whole process is closely monitored.

Has the process of gender transitioning changed your interpretation of “transition”?

Transition used to be a concept that involved going from one point to another. But now I would say that it’s more like leaving or starting from the status quo, it does not necessarily mean that you know where you would finally end up at.

Transition is a process, as I always emphasise. You will find the destination in the end, and it’s totally fine even if you are not certain during the process. You may have a direction, but you can stop anywhere or change anytime. Like for me, full surgery could have been my destination, but after I started my journey, I could stop at the top surgery or at how much hormones I wanted.

I think it’s good to always remind ourselves that there’s no definite goal and even if you have one, you can change your mind during the course of transitioning. It’s always good to have that freedom and flexibility.

[1] In Hong Kong, the first documented case of Gender Reassignment Surgery was performed in 1981 in Princess Margaret Hospital (Ng et al., 1989). In 1986, a Gender Identity Team (hereafter GIT) was established as part of the sex clinic of the University Psychiatric Unit of Queen Mary Hospital to address the growing number of people seeking the procedure.

https://gender-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2013/02/…