As long as hydrogen production relies heavily on fossil fuels, the policy will distract South Korea from its 2050 carbon neutrality strategy and end up emitting enormous additional greenhouse gases. To keep the net-zero pledge on track, South Korea should adopt a renewable-energy based hydrogen scheme by drastically cutting down its reliance on fossil fuels.

The “wag the dog” diversional strategy – a metaphorical expression popularised by a 1997 Hollywood blockbuster of its same name – does not only exist in US power politics. The story of South Korea's hydrogen scheme also saw the small “tail” wagging the “dog”, distracting attention away from a bigger, more important issue with something of lesser significance. The scheme, which has been developing and evolving over the last four years, is a symbolic case that shows how industrial needs and interests have spun and distorted the original rationale of clean hydrogen as a carbon emission-free and climate-friendly technology in South Korea’s energy transition.

Background

The idea of the hydrogen economy, which quickly captured the attention of South Korea’s government and energy industry, in the beginning was regarded as a future energy technology rather than an industrial opportunity. However, after the introduction, in January 2019, of the “Hydrogen Economy Promotion Roadmap”, the government released in November 2021 the “First Basic Plan for the Implementation of the Hydrogen Economy” that describes a mega-scale hydrogen scheme.

Hydrogen is more an “energy carrier” rather than an “energy source”. Unlike renewable energy or fossil fuel, hydrogen does not occur naturally in large quantities. As hydrogen is bound up in nature such as in water or hydrocarbon molecules, its extraction requires energy-intensive sources like renewables, fossil fuels, or nuclear power. Considering the massive energy needed to produce hydrogen itself, hydrogen should be considered a means of energy storage that can later be used for example in a fuel cell to produce electricity. The question of energy efficiency is a major issue here, because substantial losses arise from the conversion processes involved.

Despite these issues, the discussion about hydrogen was initiated mainly because of the aggravating climate crisis. As the previous government under President Moon Jae-in (until May 2022) pushed forward its new green policy and commitment to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, expectations for hydrogen began to run high. While hydrogen does not emit greenhouse gases or other air pollutants when being burnt, some experts also expected that hydrogen-run fuel cells and turbines could supplement and improve the flexibility of renewables and thus increase grid stability.

At the beginning, the initiative was driven by the 2050 carbon neutrality goal. However, what ultimately shaped the current hydrogen scheme were the expectations and needs of the country’s industry. As no countries have established an overall value chain for hydrogen – from production stage to distribution and consumption – the South Korean government has been seeking relevant opportunities for industry stakeholders. To align with the government's ambition, conglomerates including Hyundai Motors and SK are committed to investing South Korea Won (KWR) 43 trillion (USD 30 billion) in their hydrogen projects at least until 2030.

Finally, the “First Basic Plan for the Implementation of the Hydrogen Economy” was published in November 2021. It aims to expand South Korea’s hydrogen production to 28Mt by 2050, which outnumbers the current supply by 127 times. In the short run, Korea plans to supply 3.9Mt of hydrogen by 2030.

![]()

How Industrial Needs Sway the Hydrogen Economy

The steep rise of hydrogen production in South Korea's plan may come as a surprise and even a shock to experts. According to the government’s plan, hydrogen will be responsible for a third of the total energy consumption in 2050. This is entirely incompatible with the limited role of hydrogen in the existing concepts. To treat hydrogen as an “energy carrier” raises many doubts.

What’s even surprising is that, through the confirmation of the roadmap, the government overturned its existing hydrogen supply plan under the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), which had been updated a month before. The government doubled the hydrogen production/consumption expectations (1.9Mt) of the updated NDC. The incremental production increase was propelled by “grey” hydrogen (generated from fossil fuels) and import, while the demand side was driven by the power sector.

As the result, according to the NDC, by 2030, the domestic production will still heavily rely on fossil fuel-based hydrogen for 87% of the whole supply. Hydrogen was considered climate-friendly as aforementioned, but its impact on the climate varies a lot according to which energy sources are they based on. South Korea's current hydrogen scheme, which was promoted as an “establishing new market”, was an extension of the fossil fuel value chain. Even renewable energy-based green hydrogen is projected to rise fast, after 2030, fossil fuel-based hydrogen still consists of 40% of domestic hydrogen production by 2050.

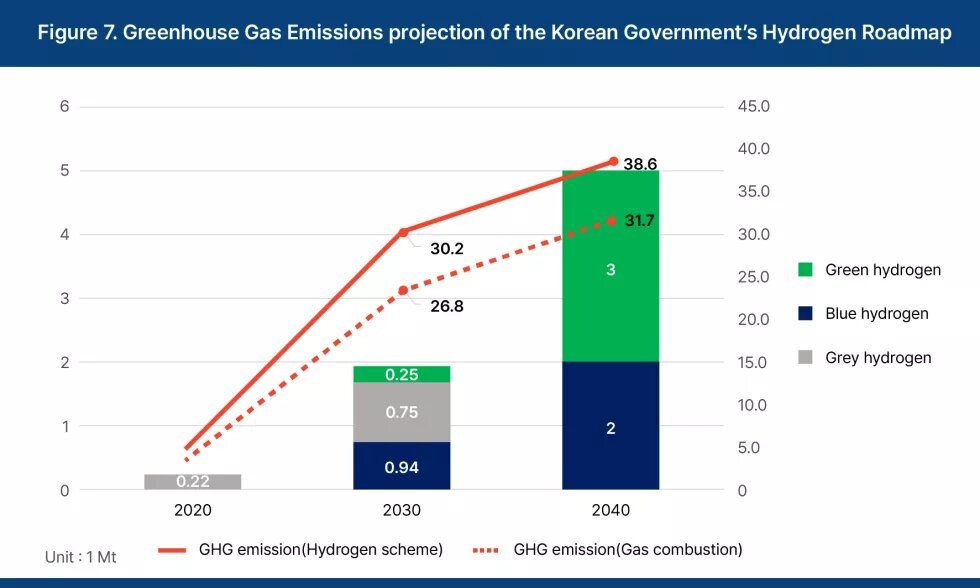

For that reason, the hydrogen scheme has gone far away from the 2050 carbon neutrality initiatives of South Korea. With reference to the methodology of a Cornell and a Stanford University study, Solutions For Our Climate, a Seoul-based climate advocacy group specialising in energy policy, estimated the government's additional greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 based on the current announcement. The analysis showed that South Korea's fossil fuel-oriented hydrogen scheme could end up emitting 30.2 MtCO2eq additionally. By using fossil-based hydrogen, it would even emit 3.4 MtCO2eq more than burning fossil gas directly to acquire the same amount of energy.

Even fossil 'blue' hydrogen – which makes up most of the fossil fuel-based hydrogen of South Korea – is challenged for its actual contribution to mitigating CO2eq. Blue hydrogen was recognised as “clean” by cutting CO2 emissions through Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies. However, the Cornell and Stanford research suggested that blue hydrogen still emits 88% to 91% of the greenhouse gas produced from grey hydrogen. A major component of the problem consisted of methane’s fugitive emissions throughout the overall value chain of fossil gas. As a major component of fossil gas, methane has a potent global warming potential in the short run, reaching 86 times that of CO2 in a 20-year timeframe. On top of that, capture rate restrictions of CCS and additional combustion emission make 'blue hydrogen' carbon-intensive hydrogen.

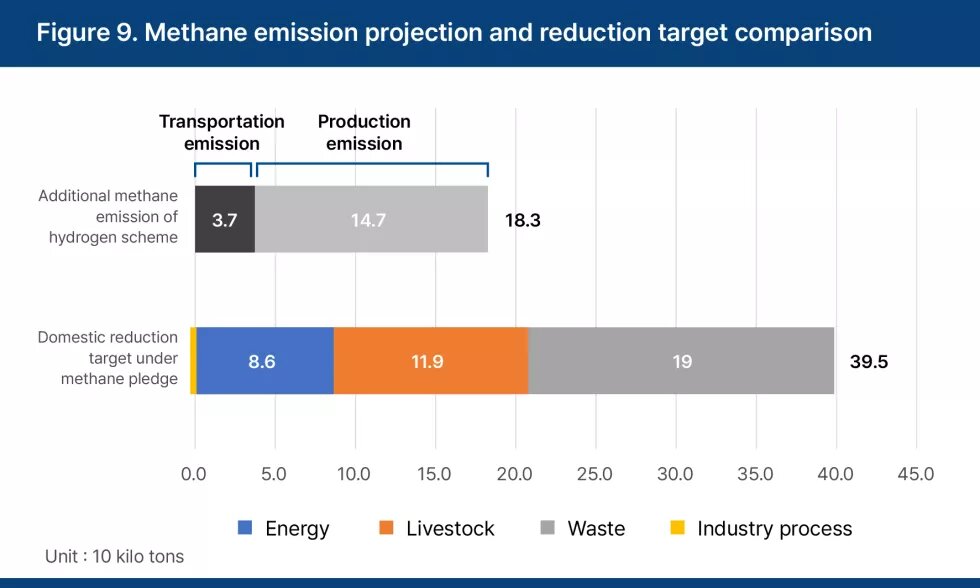

If the methane emission from the hydrogen economy is looked at independently, South Korea's hydrogen scheme may also come into conflict with the methane reduction target under the Global Methane Pledge, which the government signed in 2021. Signatories of the Pledge committed to collectively reducing global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. However, South Korea’s hydrogen scheme is expected to emit about 183 kilotons of additional fugitive methane in 2030, which is almost half of the country’s 2030 methane reduction target of 395 kilotons. Eventually, domestic efforts from relevant stakeholders to reduce methane emissions could be in vain if the government proceeds with its hydrogen economy.

Even though the hydrogen discussion was started as an effort to cut greenhouse gas emissions drastically to meet the 2050 carbon neutrality goal, the final destination of the roadmap, as has been formulated by the government of South Korea, is expected to create massive additional emissions. Industrial needs seem to have wagged the grander hydrogen scheme successfully.

Shadows of Fossil Fuel Risks

At present, South Korea is paying its cost for its high reliance on fossil fuels. The current power generation relies heavily on coal and gas, which account for up to 70% of total power generation. As gas prices soared due to post-pandemic economic recovery and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, KEPCO, the state-owned utility company, is reporting a massive operating loss. As long as South Korea is reluctant to transition to renewables which will become cheaper in the near future, the whole burden would be shouldered by its citizens and future generations.

Considering the hydrogen scheme’s reliance on fossil fuel-based hydrogen, the current fossil fuel crisis in the power grid could also extend to the grey- or blue-centred hydrogen economy that itself is part of the fossil fuel value chain.

As gas prices skyrocketed in Europe, fossil hydrogen has already lost its price competitiveness compared to green hydrogen. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), the levelised cost of green hydrogen (LCOH) has become cheaper over the past two years, within the range of USD4-6 per kg, while the cost of grey hydrogen and blue hydrogen soared from USD1-3 to USD6-12 per kg. Even though the gas price is expected to recover to the previous level in the near future, the trend would not change. The Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that even with the lowest gas price, green hydrogen will secure price competitiveness, following the decline in renewable energy prices.

As long as South Korea sticks to the current fossil fuel-oriented hydrogen scheme, the cost risks of fossil fuel will be transferred to hydrogen consumers, such as Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV) users and retail electricity consumers, while the revenue still goes to the fossil industry.

Given that the current fossil fuel-oriented hydrogen scheme will not only slow down the country’s green hydrogen from becoming competitive, but also expose its hydrogen industry to various risks related to fossil fuels, the government should drastically cut down its reliance on fossil fuels.Additionally, the overall supply and consumption target for hydrogen needs to be adjusted realistically. Hydrogen surely has a role in the decarbonisation of the steel industry by replacing coking coal. However, considering the usage of hydrogen in the power sector, as well as its limitations as an energy carrier, its role should be restricted to supplement the variability of renewables. To do so, while reevaluating the proper portfolio of hydrogen on the grid, efforts should be devoted to install as much renewable energy as possible domestically and internationally. The challenges of renewables – especially domestic permission hurdles and fossil-oriented public finances' investment overseas – must be addressed before stepping up to the next stages of the energy transition which would involve converting excess electricity from renewables to hydrogen.