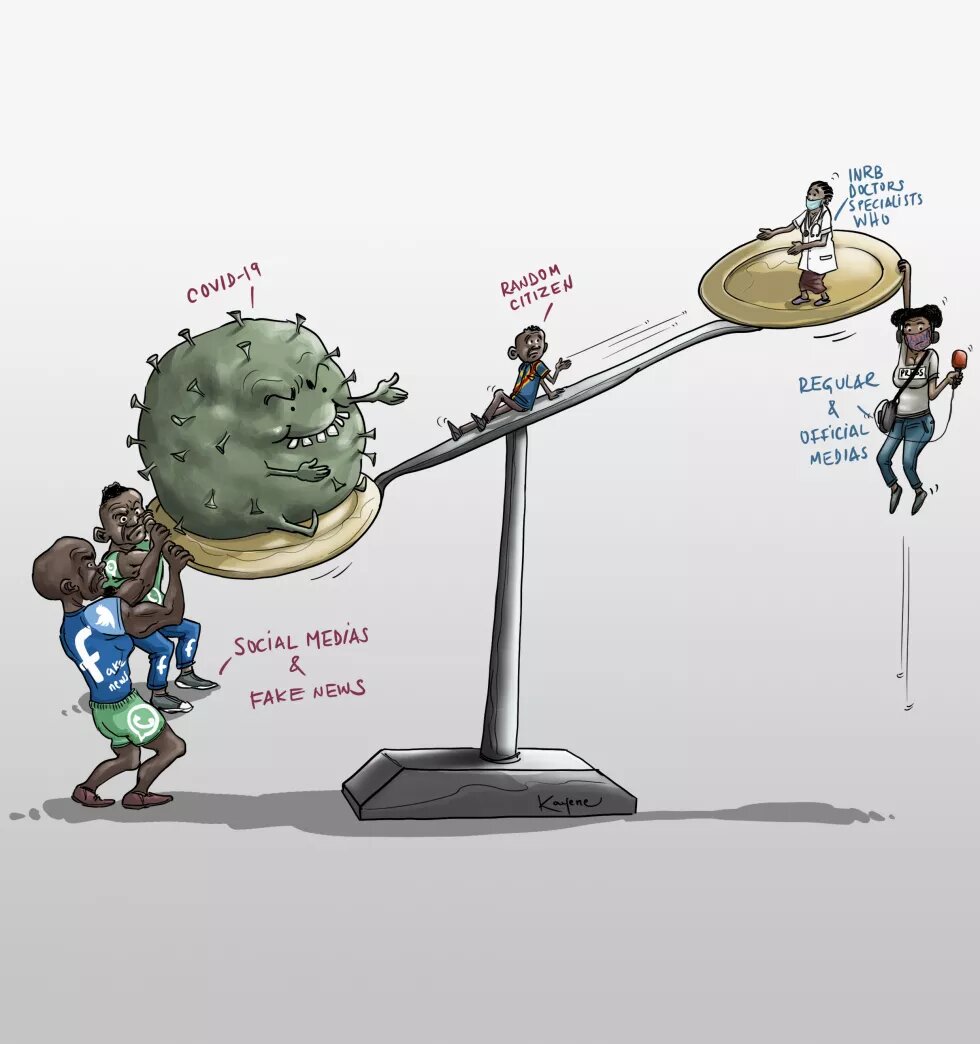

False news is a major threat to the Covid-19 response in DRC. Government distrust, lockdown, and increased social media access accelerate the spread of misinformation and disinformation in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

At the Hôpital Provincial Général de Reférence de Bukavu (HPGRB) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), most of the patients infected with Covid-19 come in only after they’ve delayed for too long, says Pacifique Mwenebantu, a doctor and researcher. Mwenebantu believes that these patients are the victims of coronavirus-related false information, which has proven to be one of the biggest challenges facing the DRC, a country of more than 89 million people in the heart of Africa.

“It is still too hard to convince the ordinary Congolese that coronavirus exists,” says Rodriguez Katsuva, founder of Congo Check, the first fact-checking organization in DRC, which has partnered with Facebook to identify misinformation and disinformation online. (Misinformation is false information, while disinformation is false information deliberately created to cause harm.) Honneur-David Safari, editor in chief of online publication La PrunelleRDC, agrees. Despite being an editor covering the pandemic, “I still work hard to make my mom believe that the coronavirus is real,” he says.

In some ways, the DRC’s past has prepared its citizens for the current pandemic. For example, the country’s fight with Ebola taught citizens some baseline knowledge of contagious diseases and prevention. But this is not enough.

Fake news has polluted Congolese social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp, and Instagram. Some conspiracy theories deny that the pandemic exists. Others state that Covid-19 “is only a white disease,” or that the government is working with hospitals to kill potential Covid-19 patients and increase the death count in order to receive more financial aid. Reports of a supposed low fatality rate and a lower contamination rate compared to Ebola have made DRC citizens less cautious. Many say that even if the virus were real, muvuke (a traditional remedy made with aromatic plants such as eucalyptus and lemon) is enough to cure it. A new word borrowed from French – coroniser – has emerged, meaning fake cases put in quarantine to help the state fabricate statistics to access money.

Factors and actors behind disinformation in DRC

Many factors are responsible for the rampant spread of fake news in DRC. First, citizens feel great mistrust toward government officials delivering information about the new virus. Contradictions regarding the nationality of the first case – he was alternately identified by the National Health Minister Eteni Longondo as Belgian, then as a Congolese living in France – convinced the population that the case was false. Similarly, Théo Ngwabidje, the South Kivu States governor in eastern Congo contradicted the National Institute in Biomedical Research (INRB) regarding the number of cases.

On the top of that, the lack of transparency in fund management fueled narratives that state authorities are enriching themselves through Covid-19 and stood to profit by declaring false cases. “Government official communication still lacks the context-based language, making low and moderately digitally literate citizens more vulnerable to any third narrative that will appear to make sense or touch their emotions,” says a journalist who asked to remain anonymous.

The lockdown has also exacerbated the flow of false information. In the face of uncertainty, societal and religious leaders play an important role in informing communities in DRC. Though community leaders are not immune from spreading misinformation, in general they remain one line of defense against outrageous rumors. But Covid-19 containment measures demand the closure of churches, schools, and universities, cutting off Congolese from these trusted societal leaders, according to Tony Shindano, a doctor at HPGRB and a member of the eastern Congo Ebola and Covid-19 response team.

At the same time, social media access is becoming more widespread, even though not everybody has access to quality information. Mobile internet companies have reported over one million new users in the first trimester of 2020 and recent statistics show that 84.5 percent of the population uses Facebook. Alain Darel Bagula, executive director of the local non-profit Wokovu Way, adds that Facebook’s Free Basics connectivity plan (a plan providing free text navigation and messaging) has also facilitated increased access to social media. Combined with the lockdown measures, this allows people, especially youth, to see and share unverified information – framed to touch the emotions and capitalize on existing suspicions – without an opportunity for rebuttal from legitimate sources.

Finally, intentional disinformation is also being spread. Cosmos Bishisha, the Health Provincial Minister of South Kivu, says that opposition parties use misleading messages to stoke distrust towards the government's ability to respond to the situation. And a recent social media monitoring report on DRC from Insecurity Insight shows that misinformation has increased community mistrust toward humanitarian and foreign aid.

One image showcased in the report says “vaccin na bino, awa te” in Lingala, a language used in DRC. In English, this means “your vaccine, not here” – and the image, which was shared over a thousand times in the run-up to a European Union delegation visit to the DRC with the goal of bringing humanitarian aid in June. The arrival of the visitors - among them the foreign affairs ministers of France and Belgium - coincided with the news that two local Congolese staff at the EU Delegation in Kinshasa had tested positive for Covid-19. Readers of a popular internet site instead were given the impression that the visitors had imported the virus.

Victims of disinformation in DRC

Anyone can be tricked by disinformation, according to Congo Check founder Rodriguez Katsuva. “I see some politicians, some journalists, as well as some of the elite fall into the trap of conspiracy theories,” he says. Human rights activist Marcellin Chirha, however, emphasizes that less critical and digitally literate citizens – especially those who lack the ability to cross-check information or whose network is regularly exposed to negative information – are the most vulnerable.

Women in particular may find it difficult to combat disinformation, according to Dr. Aziza Aziz Suleyman, a gender activist, blogger, and expert in reproductive health. Congolese women use communication channels that consist of groups like Facebook, WhatsApp or virtual religious groups. These women tend to be more vulnerable if the group has a dominant opinion and members are unable to question the explicit and implied statements. One sad result of this misinformation was the death of three children in Kinshasa after being given Kongo Bololo (a traditional medicine made of shredded leaves, used in DRC for liver infections) mixed with lemon juice to protect from and cure Covid-19.

Fighting against misinformation

To combat this growing issue, private companies, government, and other organizations have started using new tools. In March, Health Minister Eteni Longono launched MINSANTE TV to deliver accurate Covid-19 news. Government officials also established the web portal STOP CORONA VIRUS RDC to provide real-time official and fact-checking information from the country’s pandemic response team. According to Popole Muyembe, who is responsible for the response team’s communications, the Covid-19 response team has been correcting false information on social media and also broadcasts on local radio and television.

“We keep doing it with question-and-answer sessions and expert advice in order to give a chance to the rural and urban audience that still rely on radio as the means of information.” adds Raissa Kasongo, Program Manager of Radio Maendeleo, the community radio ranked closest to the community by Barza Grand Lac in 2019. “The biggest challenge we are facing now is that we have been obliged to remove some of the programs that were deemed not urgent in order to multiply programs that fight disinformation.”

The non-profit sector has also played a key role. Wokovu Way, for example, has been conducting door-to-door informational visits to provide further clarification of official information regarding prevention of Covid-19. Christian Shombo, the Ebola field officer from the International Office of Migration in DRC said that the organization has considered using motorized caravans and flyers to distribute in the field.

The hope is that these efforts can make a difference for communities, experts, doctors, and citizens, and that with many channels to access better information, fewer will wait to go to the clinic until it is too late.