The first plastics imitated ivory and silk and attracted just a limited market. Things took off after World War II with the rise of PVC. Cheap plastics soon conquered the world.

Plastics are part of the everyday life of billions of people and are used extensively in industry. Over 400 million tonnes are produced globally every year. But what exactly is plastic? The word refers to a group of synthetic materials made from hydrocarbons. They are formed by polymerization: a series of chemical reactions on organic (carbon-containing) raw materials, mainly natural gas and crude oil. Various types of polymerization make it possible to produce plastics with particular properties: hard or soft, opaque or transparent, flexible or stiff.

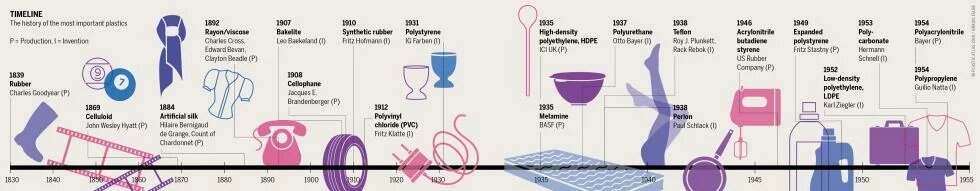

The first plastic was presented at the Great London Exposition in 1862. Called “Parkesine” after its inventor, Alexander Parkes, who made it from cellulose, this organic material could be shaped when it was heated and retained its shape on cooling. A few years later, John Wesley Hyatt developed celluloid, transforming nitrocellulose into a deformable plastic by treating it with heat and pressure and adding camphor and alcohol. It replaced ivory and tortoiseshell in billiard balls and combs, and was destined for a bright future in the film industry and photography. In 1884, the chemist Hilaire de Chardonnet patented a synthetic fiber known as “Chardonnet silk.” Its successor, rayon or viscose, is a semisynthetic plastic made from chemically treated cellulose - which is cheaper than natural fibers such as silk.

This and other early plastics were made from natural raw materials. It would take another 40 years before a completely synthetic plastic was developed. In 1907, Leo Hendrik Baekeland improved on phenol-formaldehyde reaction techniques and invented Bakelite, the first plastic that contained no naturally occurring molecules. Bakelite was marketed as a good insulator and a durable and heat-resistant material.

Five years later, Fritz Klatte patented a material known as polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC, or vinyl. Until the middle of the 20th century, plastics occupied a relatively small market niche. The trigger for the mass spread of PVC was the discovery that it could be made from a waste product of the petrochemicals industry. The chlorine resulting from the production of sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) could be used as a cheap feedstock.

This marked the start of the rapid and uninterrupted rise of PVC. In World War II, demand rose significantly because it was used to insulate cables on navy ships. Although it was increasingly known that PVC production harmed both the environment and human health, the petrochemicals industry took advantage of the new possibilities to turn a waste product into profit. PVC has since become the most important plastic in a wide range of household and industrial products.

Alongside PVC, polyethylene has also gained acceptance. Invented in the 1930s, it is used to make drink bottles, shopping bags and food containers. The chemist Giulio Natta developed polypropylene, a plastic with similar properties to polyethylene. Gaining popularity in the 1950s, it is today used for a range of everyday products such as packaging, child seats and pipes.

At the time, the positive image of plastics contributed to the boom in their use. Plastics were seen as trendy, clean and modern. They squeezed out existing products and muscled their way into almost all areas of life. Today, PVC, polyethylene and polypropylene are the most widely used plastics in the world.

To improve their properties, plastics are often mixed with chemical additives such as plasticizers, fire-retardants and dyes. Many of these additives make the material more flexible or durable. But they may damage both the environment and health. They can escape from the material and enter the water or air, ending up in our food. They can also be released when plastic is recycled.

A new generation of plastics can be made from bio- polymers such as maize starch. For example, a completely new production process has made it possible to make a biodegradable plastic from the shells of shrimp and other crustaceans. This modifies chitin from the shells to make a polymer called chitosan. The developers at McGill University in Canada hope for a bright future based on the 6–8 million tonnes of crustacean waste produced every year. This and other plastics based on natural raw materials are already being used to make drinking straws, disposable plates and cups, plastic bags and food packaging. But it is doubtful whether they can contribute to solving the plastic crisis.

This article is a part of Plastic Atlas and was first published on boell.de by Alexandra Caterbow and Olga Speranskaya.