Population policies should be devised within a reproductive justice framework as women’s bodies have been easily objectified and utilised for national development when maternity is only understood as a woman’s duty. South Korea’s current pronatalist approaches have failed to address the real issues of low fertility trend.

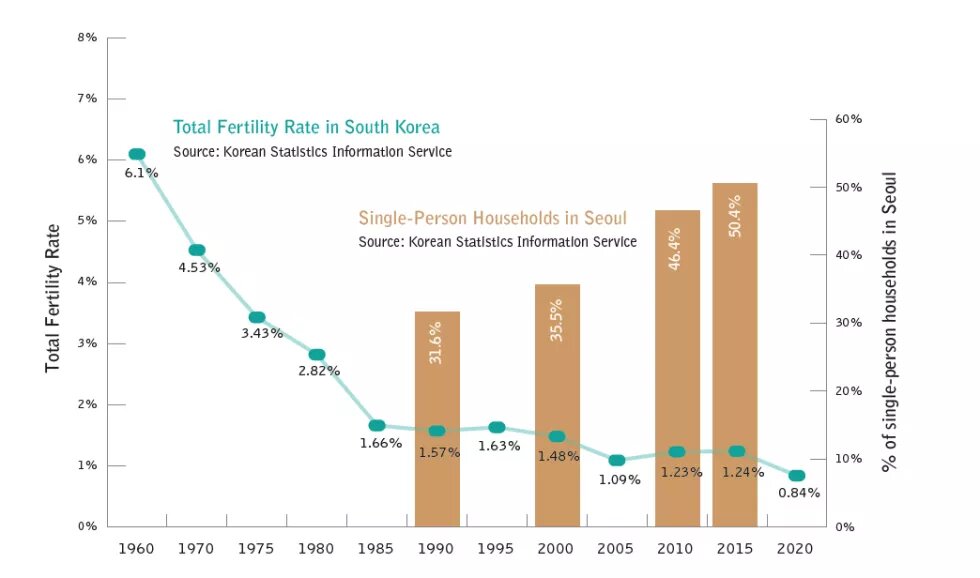

One of the current, critical issues facing Korean society is the ultra-low fertility trend. In 2020, the total fertility rate in South Korea reached 0.84 – the lowest in the world.[1] Although the Korean government has aggressively promoted childbirth since 2005 when they defined the low fertility rate as a serious national crisis, the total fertility rate has dropped continually from 1.48 in 2000 to 0.84 in 2020. Under these circumstances, this essay critically examines why this rapid demographic shift has occurred and how the South Korean government has reacted to the population change. By focusing on the impacts of the government’s population policies on women’s bodies and reproductive rights, this essay argues that the policies only reflect a concern for numbers – specifically of population growth – rather than the living conditions and quality of life of individuals; as such, the current policies are not only ineffective but also fail to guarantee the reproductive health and rights of the Korean people.

Population Policies from the 1970s to the 2000s

In contrast to the current low fertility trend, as recently as 30 years ago, South Korea was more concerned about overpopulation. In the 1960s, the total fertility rate in South Korea was more than 6.0. To reduce the fertility rate, the government adopted a “family planning programme” as part of its Economic Development Plan in 1961 and enacted the Mother and Child Health Act in 1973, which was the legal basis of the “family planning programme.” At that time, South Korea could receive international aids such as USAID by following the recommendations of a birth control campaign and importing contraceptive technologies. The representative slogan of the national campaign was “give birth to only two children, regardless of sons or daughters”. As part of these new population policies, families who had three or more children had to pay an extra residence tax and additional fees for the country’s national health insurance. Under the antinatalist policies of this era, abortion was widely practised and encouraged by the government even though it was technically illegal. Women could easily access abortion and sterilisation procedures at family planning clinics. As a result, the total fertility rate dropped to 2.8 in the 1980s – and then further to 1.6 in the 1990s. Thus, South Korea’s “family planning programme” of the 1960s and 1970s has been cited as one of the most successful examples of a population control project (Hernandez, 1984).

However, as the total fertility rate continued to dip in the 2000s, the direction of population control policies dramatically shifted from an antinatalist approach to one that focused on boosting childbirth. In 2005, the South Korean government enacted the Framework Act on Low Birth Rate in an Aging Society and tried to promote childbirth by targeting single individuals and newly married couples by providing newlyweds with housing benefits, childcare allowances, and infertility treatment subsidies. Although the South Korean government changed the direction of the nation’s population policies in the mid-2000s, what has not changed is their primary target: women.

Under the nation’s antinatalist policies in the 1960s and 1970s, women were considered responsible for lowering fertility rates and were the main targets of sterilisation campaigns. When the government reversed its policies in the 2000s – and the discourse on Korea’s low fertility rate crisis expanded – single women were singled out as the main culprit. For example, in mass media throughout the 2000s and 2010s, the low fertility rate trend was portrayed as a type of dystopian future. Op-eds and media pieces painted stark pictures of labour shortages, higher life expectancies, a growing number of elderly people, and the individual and societal burdens of caring for an ageing population. In 2016, the Ministry of the Interior launched the “birth map” website, which showed the total number of women aged between 15 and 49 (childbearing age), and fertility rates by city districts and regions. However, no data about the number of childbearing-aged men was shown on the map. In Korean society, since all fertile-aged women are considered potential mothers, the issue of low fertility became all women’s responsibility – and their bearing of children was viewed as an obligation that was crucial for the nation’s survival.

Gender Inequality Aggravated by Low Fertility

To explain South Korea’s unprecedented low fertility trend, many scholars have analysed changes in the nation’s demographics, family structures, economic structures, and the labour market. Using previous research on demographic changes, feminist scholars in particular have argued that the low fertility trend cannot be discussed without taking into account the double burden placed on Korean women. Stereotypical gender roles and norms (such as those that categorise males as breadwinners and females as caregivers) have been weakened in the last few decades, and more women are attaining higher levels of education and participation in the labour market. For both men and women, a career-oriented life course has become a standard. The expansion of family-friendly policies tend to support married women and mothers by minimising the conflicts between work and family, but has failed to address why women are expected to perform most household chores. According to “2022 Men’s and Women’s Lives Through Statistics, the gender gap in the labour participation rate, employment rate, and wage levels in South Korea have yet to be relieved. For example, women earn 72.6% of what men do, and the women’s employment rate is 51.2%, which is 18.8% lower than that of men. Furthermore, the data show that 17.4% of married women leave their jobs due to childcare (43.2%), marriage (27.4%), and childbirth (22.1%) (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 2022).

Under these circumstances, the number of people who are delaying marriage are childless and living in single-person households has been gradually increasing in South Korea. Moreover, perceptions regarding marriage and childbirth have rapidly changed among young people. For example, in a survey by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs in 2018, 19.5% of the single female respondents aged 20 to 44 said that they should have a child, 28.8% said that having a child would be better than being childless, and 48.8% didn’t regard having a child as a matter. The attitudes of single men aged 20 to 44 were similar. In other words, almost half of the single men and women aged 20 to 44 in South Korea no longer find marriage and childbirth their essential life tasks. As these attitudes about childbirth have changed, the actual single population has also increased. As shown in Figure 2, 31.6% of Seoul’s population that was aged 20 to 49 was single in 1990, but this number increased to 50.4% in 2015. Although the nuclear family model – consists of a heterosexual couple and two children – is still a strong social norm, the numbers tell a different story and indicate that a single-person household has become a “new normal” in South Korea.

While the government has invested more than South Korea Won (KRW) 225 trillion (USD 155.7 billion) over the last 15 years in a bid to boost the number of newborn babies, the fertility rate has not rebounded. Thus, recognising the country’s demographic shifts, new social policies for supporting diverse forms of families are more urgently needed than childbirth promotion policies that maintain the norm of the heterosexual nuclear family.

Reproductive Health and Rights Under South Korea’s Pronatalist Policies

Although the South Korean government has emphasised the protection of maternity health in its reproductive and family planning laws, its pronatalist policies have ironically put reproductive health and rights under threat. The government has been expanding supports for the use of assisted reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF), while limiting the access to contraceptives and abortion. In 2005, the government removed contraceptive technologies (including sterilisation surgeries, oral contraceptive pills, and emergency contraceptive pills) from the national health insurance. Any support for contraceptive methods would be deemed in conflict with the country’s new pronatalist policies. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health and Welfare acknowledged its plan to establish abortion prevention policies. As a result, the criminal codes on abortion were revived, and accessibility to abortion services became very limited. The enforcement of these codes continued until 2019 when a Constitutional Court decision finally decriminalised abortion. However, the government remains reluctant to support abortion-related health care and services because lawmakers believe that they contradict the country’s childbirth promotion campaign. For example, the government expanded paid maternity leave in 2012, including in cases of miscarriage and stillbirth, but excluded paid leave for abortion procedures. Moreover, while abortion is now legal in South Korea, abortion procedures are still not covered by the national health insurance.

Reproductive justice recognises both the right to have a child and the right to not have a child as well as the right to parent children in safe and healthy environment (Ross & Solinger, 2017). Yet, in each phase of its reproductive health care policies, the Korean government has only partially recognised its citizens’ reproductive rights. During the period when it sought to reduce population growth, contraception and abortion were supported by lawmakers, but fertility treatments were neglected; conversely, since the 2000s during which ultra-low fertility rates have been recorded, various restrictions have been imposed to impede contraception and abortion, and fertility treatments have been encouraged. Indeed, one can argue that the country’s current pronatalist policies violate reproductive rights because they only focus on the number of babies born rather than individual women’s bodies, experiences, and needs. Women’s bodies and reproductive capacities become objectified as tools for population growth. To effectively guarantee one’s choice and rights to have children or not have children, affordable medical services, education, and information should be provided in a way that guarantees every individual's reproductive rights and health.

Conclusion

Considered a basic human right, reproductive rights are described and enshrined in various international human rights treaties. The South Korean government should not simply focus on forced-birth policies to reverse declining population growth; instead, they must prepare comprehensive policies that guarantee the reproductive health and rights of all individuals. However, the current government is heading in opposite direction. President Yoon Suk-yeol pledged to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF) and blamed the low birthrate on feminism during his election campaign. After he was elected, the plan to abolish the MOGEF and establish a new department of Population, Family and Gender Equality under the Ministry of Health and Welfare was announced on 6 October 2022. The replacement epitomises the government’s anti-feminist sentiment. Many feminist scholars and activists have expressed concerns that abolishing the MOGEF could reduce all the policies related to gender equality. Also, the name changing from “Gender Equality and Family” to “Population, Family, and Gender Equality” sweeps gender equality issues under the umbrella of population policy rather than considering it as part of reproductive rights. The concept of reproductive rights is never fixed, and it has and will always evolved with the feminist movement. In South Korea, the defense of reproductive rights remains a battle in progress.

[1] A total fertility rate of 2.1 is estimated as the replacement level, a fertility rate below 2.1 is considered a low fertility rate, and a number below 1.3 is defined as the “lowest-low fertility” rate (Kohler et al, 2002).

References

Hernandez, D. J. 1984. Success or failure? Family planning programs in the Third World. Greenwood Press.

Kohler, H. P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. 2002. The emergence of lowest‐low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and development review, 28(4), 641-680.

Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2018. The 2018 National Survey on Fertility and Family Health and Welfare.

Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. 2022. 2022 Men’s and Women’s Lives Through Statistics.

Ross, L., & Solinger, R. 2017. Reproductive justice: An introduction (Vol. 1). University of California Press.