Forced to follow a “no vaccine, no classes” policy, the Philippines has implemented distance-learning programs that exacerbate existing inequalities.

Eighteen-year-old Erika Marie Custodio, a college freshman, was scouring the internet for tablet and laptop giveaways when she discovered Shopee Bubble, a game where players can earn virtual “diamonds” to be exchanged for prizes. Now, she plays every day.

Custodio is determined to earn at least 600 diamonds, which she can exchange for a tablet to use for her online classes at the Emilio Aguinaldo College in Cavite, a suburb outside of Manila.

Right now, only halfway to her goal, she has to make do with the 5-inch screen of her cell phone as her “classroom.” Such a tiny screen makes it difficult to type questions or comments in the chat box when tuning in. “I feel like I’m missing out on classroom discussions,” said Custodio. To cope, she downloads the lesson plans on her phone and then re-writes them on paper to make it easier to read. All in all, she spends about 9 hours a day studying.

“My eyes are strained and my back aches from sitting in the corner for a long time but I don’t have a choice—I don’t have my own room,” she said. “By the end of the day, I am totally spaced out.”

“No vaccine, no classes”

Custodio is one of the roughly 28 million Filipino students who have been impacted by school closures meant to minimize the spread of COVID-19. Filipino students have not been inside a classroom since March, when President Rodrigo Duterte declared a nationwide public health emergency. Government education bureaus had planned to eventually allow face-to-face classes in areas with low COVID-19 infection rates but then, in May, Duterte created a “no vaccine, no classes” policy, effectively keeping schools closed indefinitely.

It’s bad news for a country where “there was an education crisis even before [the pandemic],” said Isy Faingold, chief of education at UNICEF Philippines. In the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a global survey on the knowledge of 15-year-old students, the Philippines ranked last among 79 countries in reading comprehension. The country’s performance in mathematics and science was also among the lowest in the study and the PISA report indicated that more affluent students outperformed those from disadvantaged backgrounds. “This pandemic aggravated [the education crisis],” said Faingold, which believes it is critical that “the school year start immediately and reach the most disadvantaged children as we progressively move towards face-to-face learning.”

“My eyes are strained and my back aches from sitting in the corner for a long time but I don’t have a choice—I don’t have my own room”

Studies from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have shown that when education is disrupted by emergencies like disease outbreaks, children are more likely to drop out of school completely. The agency also warned that delaying the opening of the school year would further widen the education gap and would have long-term repercussions on children’s development. “Distance learning is not perfect and it is not going to be easy, but it is better than nothing,” Faingold added.

With in-person classes impossible, the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), which oversees colleges and universities, put together distance learning options that include online platforms, offline modules, or a combination of the two, called blended or flexible learning. But distance learning has made inequities, especially around the digital divide, more apparent than ever before.

The challenges of modular learning

For K-12 students, the most common form of distance learning is “modular learning,” in which class modules are printed out for students to study on their own and submit to teachers for grading. (College students like Custodio are more likely to have flexible learning programs.)

Thousands of academic books had to be compressed and printed into hand-outs. Senate President Pro-Tempore Ralph Recto estimated that 93.6 billion pages had to be printed so that millions of students could have hand-outs for at least eight subjects. “That’s about 1,500 times the 61 million ballots we printed in the last election. That’s enough paper to gift wrap all the classrooms in the land,” said Recto. Assuming a cost of one Philippines Peso (PHP) per page, the mass printing would also require a budget of PHP 93.6 billion (USD 1.9 billion) and a shortfall of PHP 35 billion (USD 721 million) in the department’s budget.

Modular learning has created extra work for the Philippines’ 42,000 public school teachers, said Benjo Basas, head of the Teachers Dignity Coalition, a nationwide organization of public school teachers. “Are we listening to the teachers and what distance learning means for their workload and their health?” said Basas. “Currently, we have teachers begging for donations of bond paper and ink to print modules. We are not confident about the government’s plans for the implementation of distance learning.”

No signal

Despite the effort that goes into printing materials, K-12 teachers are still expected to be available for consultations either online (usually through Facebook Messenger) or by text. This requires a laptop and an internet connection, which is out of reach for many public school teachers, whose starting monthly salary is PHP 22,000 (USD 420).

Many students, too, still need the internet to do supplemental research on more complex assignments. That’s a problem, given a DepEd survey showing that, of the 6.5 million students who have access to the internet, approximately 20 percent use computer shops or other public places to go online. Worse, 2.8 million students have no way of going online at all. This is especially common in the rural areas where 53 percent of the population live and where both internet access and speed can be a challenge.

The southern Philippine province of Siargao, for example, lies within the areas that have the slowest internet connection. Provincial government data indicates that less than 30 percent of the student population have internet access and there are some 600 students in “off-the-grid schools,” which includes schools in island villages that do not have electricity and are so remote that they can only be accessed by boat.

There, lack of in-person classes is having big effects. The 500 residents of the Halian island village in Siargao have electricity only from 6pm to 9pm. Teachers must travel to the nearest urban center via motorized boat to get printed modules. It is a voyage that can take up to two hours. “Most of the residents here are fisherfolk. Many do not have sufficient formal schooling and worry [about] how they will help their children answer these learning modules when their children probably know more than them,” said village captain Elsa Tampos. Distance education cannot solve these geographical disparities.

College students struggle to find gadgets

Similarly, college students doing “flexible learning,” or a combination of online and offline programs, scramble to acquire digital devices and a stable internet connection. Some parents, especially those who are among the 27 million Filipinos who lost their jobs due to the COVID-related economic slowdown, have balked at the unplanned expense.

Custodio’s father was not laid off, but his monthly salary of PHP 20,000 (USD 500) as a company driver is barely enough to cover basics like food and medicine for her disabled 23-year-old brother. It is up to Custodio to find a way to raise funds to continue her college education and someday start a career in mental health.

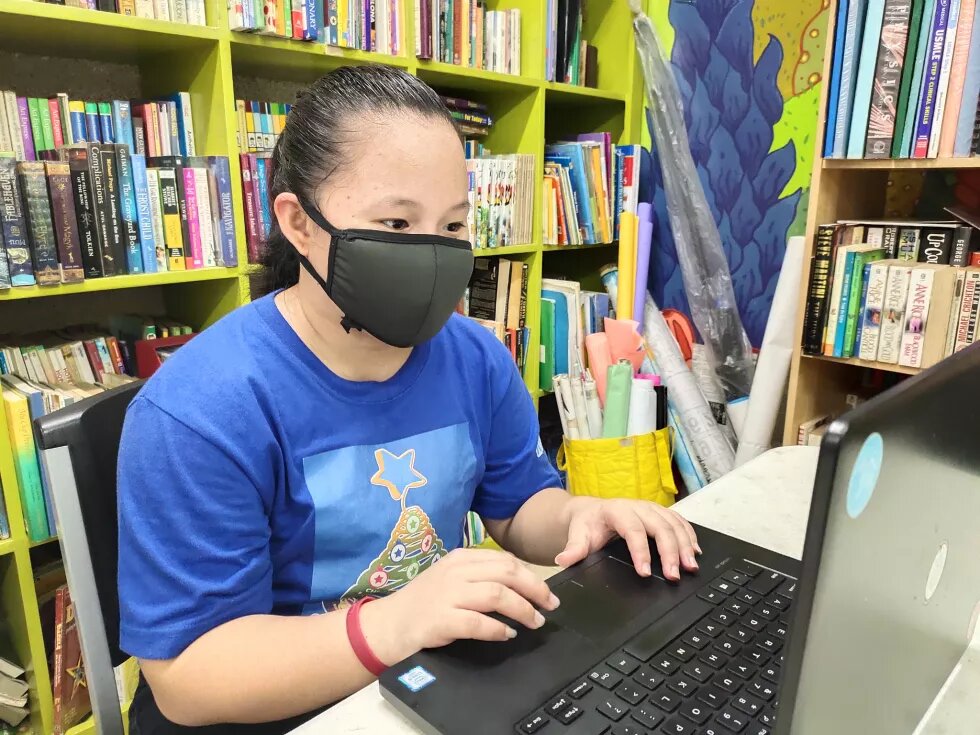

Like Custodio, 20-year-old Stephanie Ong, a medical technology major at the Chinese General Hospital College, is determined to continue going to school despite the many hurdles imposed by the pandemic. As she puts it, “What choice is there now?”

Ong's father lost his job as a truck driver when travel restrictions forced his company to suspend operations. Ong joined PisoParaSaLaptop (One Peso for a Laptop), a student-led crowdfunding initiative where strangers can donate PHP 1 to a student in need. She raised PHP 60,000 (USD 1,200+) in three weeks and bought a laptop that she shares with her two brothers, ages 14 and 8.

Still, acquiring a laptop solved just one problem. Power outages and a slow internet connection sometimes shut her out of class. Having one device as a classroom for her and her siblings inevitably results in “fights over who gets to use it when our class schedules overlap.” It’s not a sustainable solution.

“The way that things are being done is just so rushed. We need more time to prepare,” said John Lazaro, national spokesperson for activist group Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan (Organization of Progressive Youth) or SPARK. Frustrated college students are calling for an academic freeze until January 2021.

Lazaro, who is a junior in college, did not need to crowdsource funds for a laptop to attend his digital classes but he is not spared from connectivity issues. “School is just a matter of compliance now. It’s not about learning,” he said.